Coronavirus passports with vaccination info in development: report

The COVID-19 digital passport would provide a digital document showing a traveler's coronavirus test results and if they have been vaccinated.

via FOX NEWS https://ift.tt/33t9M5g

When President-elect Joe Biden steps into White House in January, he will inherit two inextricably linked crises: The worsening COVID-19 pandemic and a wide-reaching recession. As U.S. coronavirus cases are spiking to all-time highs, he will be responsible for keeping Americans safe while guiding a fragile economy through recovery.

That’s a tall order—and a somewhat paradoxical one. A fully open economy will most certainly lead to more viral spread and likely result in more deaths, while a closed economy could contain the virus but bring about even more financial hardship. And as the weather cools and fewer people want to dine, drink or otherwise spend time outside, it will become even harder to find the right mix of policies to both curb spread and keep businesses (and their employees) afloat.

Biden has already demonstrated a more hands-on approach to the pandemic than U.S. President Donald Trump. In his first order of business after being projected the winner, the President-elect established a COVID-19 advisory board to guide his thinking and work with state and local health officials. The group, Biden’s transition team says, will develop public-health strategies based on scientific information to “reopen our schools and businesses safely and effectively,” among other goals.

Still, the task at hand will be difficult, to say the least. The following five charts show what Biden and his Vice President-elect, Kamala Harris, are up against as they prepare to take the oaths of office.

The coronavirus has affected almost every country around the world. Many have taken an economic hit this year as a result. However, while citizens of other countries generally agree on how to move forward, Americans have a wide ideological divide that could make Biden’s job much harder, as presidents often draw on public support to help push their agendas forward.

A Pew survey conducted over the summer found that, among citizens of economically advanced countries struggling to contain the virus, Americans were the most polarized along party lines in their assessment of their government’s response to the virus and the economy. Furthermore, another Pew poll from October revealed that only 24% of Trump supporters said the coronavirus outbreak was very important to their vote, compared with 82% of Biden supporters. Conversely, 84% of Trump supporters said the economy was very important, versus 66% of Biden supporters.

Biden has pledged to follow the advice of public-health advisors, even if they recommend shutting down businesses. Biden’s supporters may applaud that approach, but he will find it challenging to convince the rest of the country it’s the right way to go—especially Trump’s most ardent loyalists, many of whom have shunned even basic preventative measures, like masks.

Election Day resulted in a narrower Democratic majority in the House of Representatives, while two Jan. 5 runoff elections in Georgia will determine whether the Senate remains narrowly in Republican control or gets split down the middle, with Harris casting a tie-breaking vote when necessary.

Either way, the congressional situation is a major obstacle for Biden’s agenda, writes TIME’s Abby Vesoulis. As she notes, the President-elect may get only parts of his broad plans—spanning everything from childcare to infrastructure to climate change—through a gridlocked Congress.

On the coronavirus front, Biden has called for federal relief programs—including loans for small businesses, direct payments to working families and student loan forgiveness—to serve as a financial bridge until the virus is under control. He has also proposed employing tens of thousands of COVID-19 contact tracers as a means of both curbing viral spread and chipping away at the high unemployment rate.

Federal relief programs are not new for Biden, who, as vice president to Barack Obama during the height of the Great Recession, helped shepherd a $787 billion stimulus package through Congress in 2009. But back then, he had the benefit of a significant Democratic majority in both chambers, making it easier to put the Obama Administration’s goals into practice.

The overall U.S. unemployment rate is currently 6.9%, which, while better than April’s 14.7%, still means that 10 million pre-pandemic jobs remain M.I.A., according to Nov. 6 data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). Economists have said that the jobs that haven’t returned by this point will be the hardest to claw back, in part because they are concentrated in the industries most affected by virus containment measures, like leisure, travel and hospitality.

The Trump-era employment gains may not continue at the same pace under Biden, because prolonged unemployment, especially in a weak labor market, can be harder to fix. People who have been unemployed for six months or more are about twice as likely to drop out of the labor force as to find employment, according to a U.S. Federal Reserve analysis of unemployment trends during the Great Recession. Additionally, the longer a person is out of work, the less consumer purchasing they do, which further slows economic growth.

Alarming BLS data show that long-term unemployment as a share of all unemployment is growing fast. In October, 3.6 million of the 11 million unemployed Americans—or one in three—had been out of work for six months or longer. That’s a ratio not seen since mid-2014, when Biden was VP and the unemployment rate, like today, topped 6%.

The continuing unemployment crisis has led economists to become increasingly pessimistic about when the country might return to pre-pandemic levels. Business and academic economists surveyed by the Wall Street Journal in April predicted the labor market would recover by 2022. But when surveyed again in October, 55% had extended their recovery forecast to 2023 or later.

2020 brought the country’s ongoing struggle with racism to the fore, as police brutality and other forms of violence against Black people led to nationwide Black Lives Matter (BLM) demonstrations. But systemic racism hasn’t been on display just in horrifying viral videos—it has also been apparent as COVID-19 ravaged Black communities in particular.

Systemic racism has made it harder for Black communities to achieve the wealth, access to health care and overall prosperity that white communities enjoy. As a result, Black people in the U.S. are most vulnerable to the virus itself, as well as the economic disruptions it has brought on. A disproportionate share of Black Americans have fallen severely ill from the virus. They are more likely to hold lower-wage, public-facing, front-line worker positions that put them at greater risk of exposure. And they are less likely to have accumulated savings to pay the bills if their jobs disappear. Addressing the pandemic’s health and economic effects requires acknowledging these facts, and acting accordingly.

On Nov. 9, pharmaceutical company Pfizer announced promising results from its vaccine effectiveness trials; other companies are also in late-stage trials. The stock market surged on the news, as investors predicted that the vaccine will suppress case rates and therefore expedite economic recovery.

But that won’t happen immediately, even if the vaccine is highly effective in a biological sense. Public-health strategies will continue to be critical during the time it will take to produce, distribute and widely administer a vaccine. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which is planning a phased rollout starting with high-risk populations, is anticipating that a limited number of doses will be available at first. If the rollout happens as quickly as President Trump has touted, mass vaccination could take Biden’s entire first term.

Another obstacle: for a vaccine to work, people need to actually receive it—but survey data suggest that many Americans aren’t on board. The chart below, adapted from STAT and The Harris Poll, shows that only about 58% of Americans surveyed in October plan to get a vaccine as soon as one is available—down from 69% in August. The hesitancy is even more pronounced among Black Americans, with only 43% reportedly planning to get vaccinated right away.

It’s hard to say how effective Biden will be in balancing public-health measures with the economic consequences of viral containment. Other countries have shown such a balancing is possible—Germany, South Korea and Japan, for instance, have experienced fewer deaths per capita and less severe economic losses than the U.S., as measured by gross domestic product declines since late 2019.

But it’s not an apples-to-apples comparison. Other nations benefit from a stronger consensus among citizens on the best path forward. Moreover, some have social safety nets that cushion the blows from economic disruptions. And not all countries have the added complication of deep-seated racism that has disproportionately affected minority communities in the U.S.

Still, Biden believes the government needs to do better, and he campaigned on the promise of finding middle ground. In the last pre-election debate, he suggested that health and economic goals are not necessarily in competition—that if the nation is healthy, then the economy will be, too. His challenge now will be channeling that idea into effective policy. Given that states, rather than the national government, have the most power to issue and enforce public-health rules, expect him to start by working with—or, in some cases, perhaps even pressuring—the country’s governors to follow his lead.

The freezer in your kitchen likely gets down to temperatures around -20° C (-4° F). “That keeps your ice cream cold, but it doesn’t turn your ice cream into an impenetrable block of ice,” says Paula Cannon, an associate professor of molecular microbiology and immunology at the University of Southern California’s Keck School of Medicine.

Pfizer’s promising COVID-19 vaccine, by contrast, must be stored at about -70° C (-94° F)—a temperature cold enough to harden ice cream into a spoon-breaking block of ice, and that only specialized freezers can produce.

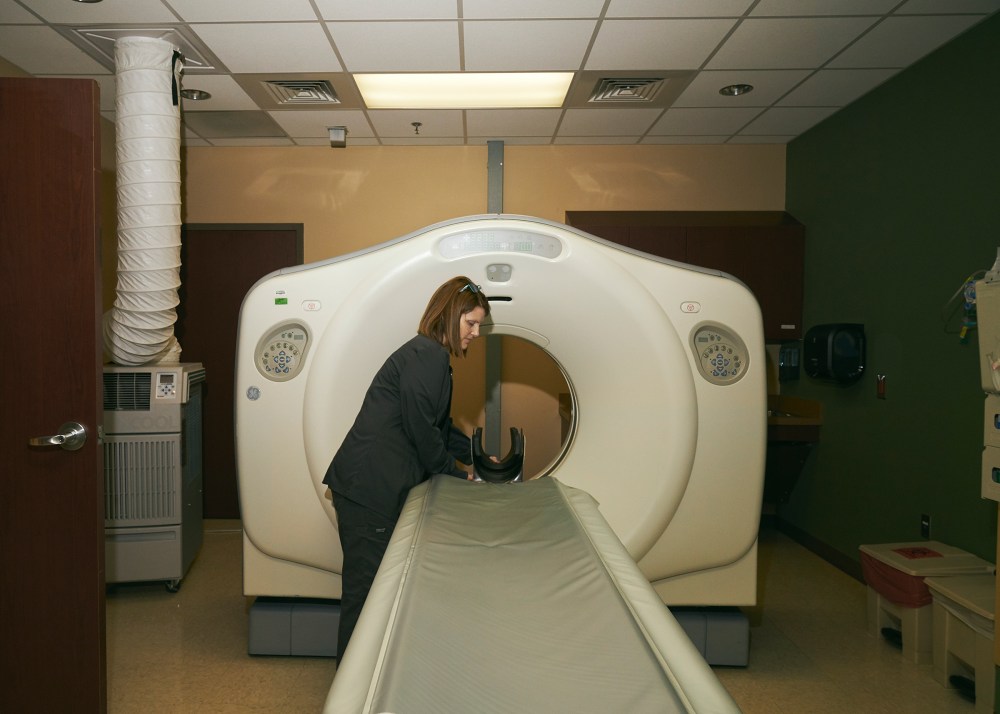

Those cold storage requirements are raising serious questions about who could get the Pfizer vaccine if it’s approved, and when. The reality, experts say, is that the Pfizer vaccine probably won’t be available to everyone, at least not right away. Large medical centers and urban centers are the most likely to have the resources necessary for ultra-cold storage. People without access to these facilities, such as those living in rural areas, nursing homes and developing nations, may have to wait for other vaccines working their way through the development pipeline.

Pfizer’s vaccine candidate, which has not yet been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration but is reportedly 90% effective at preventing COVID-19, uses genetic material called mRNA. If it’s not kept at extremely cold temperatures, mRNA can break down, rendering the vaccine unusable.

If the Pfizer vaccine is kept at -70° C, it can last up to six months. But many hospitals, to say nothing of community medical offices and pharmacies, do not have ultra-cold freezers, which cost around $10,000 up front and are expensive to run because of their high energy usage. Retrofitting existing freezers to reach these temperatures isn’t possible either, Cannon says. “It would be like going from a Fiat car to a Tundra truck”—the technology and energy requirements are simply different.

There may also be shortages of the type of pharmaceutical-grade glass needed to make vials that can withstand such cold temperatures, says Dr. William Moss, executive director of the International Vaccine Access Center at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. New York-based glass company Corning won a $204 million government grant in June specifically so it could increase production of its sturdy glass, which is made without boron.

Distributing the vaccine will also be difficult, since it must remain frozen during shipping. Pfizer has built a storage container that, with the help of dry ice, can keep doses cold for up to 10 days in transit without any additional freezer equipment. Periodically replenishing the containers with dry ice can buy another 15 days, but depending on how often the containers are opened, and for how long, that timeline could be considerably shorter. (Dry ice is also in short supply right now because of the increase in food delivery during the pandemic, combined with the fact that fewer people are driving and buying gas, driving down the ethanol production required to make dry ice.)

Once they’re out of the box, the shots can last for about five days in standard refrigeration. But the boxes hold from 200 to 1,000 vaccine vials, each of which contains about five doses of the shot—more than most doctor’s offices could reasonably expect to use before some doses start to defrost and become useless, as ProPublica recently reported.

A Pfizer spokesperson told TIME that the company “is committed to ensuring everyone has the opportunity to have access to our vaccine working closely with local government.” The spokesperson added that global distribution has gone smoothly during clinical trials, and that portable and under-the-counter-sized ultra-cold freezers are available for smaller vaccination sites.

“We believe all countries will be able to effectively dose patients even with our cold chain requirements,” the spokesperson said.

For mass U.S. distribution, Cannon says the most practical solution may be setting up large, centralized vaccination centers that could rapidly go through doses, rather than trying to get the jab into every doctor’s office and pharmacy nationwide. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services on Nov. 12 announced it will work with pharmacies nationwide to distributes COVID-19 vaccines for free, but it’s not yet clear which vaccines will be available through that partnership.

Some states are considering large vaccine depots, as indicated by their draft plans for vaccine rollout sent to the CDC, but such centralized hubs require additional staff, equipment and cost that some states can’t afford. Plus, in rural areas, reaching a “centralized” location may still require lengthy travel for some people. The Pfizer vaccine must also be given in two separate doses, which could be a hard sell to people who have to drive hours to get it.

Moss adds that those who need the vaccine most—like the elderly and those with prior health conditions—may be the least able to travel to get one. And distributing an ultra-cold vaccine may be a pipe dream in countries poorer than the U.S., Moss says.

“It would be extremely challenging, if not impossible, to get such a vaccine out to, say, countries and people in Sub-Saharan African and many parts of Asia, where the infrastructure is not what we have in the United States,” he says.

Pat Lennon, who oversees cold-chain storage at the global health nonprofit PATH, says ultra-cold vaccines were distributed during the recent Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, but that was an easier feat, since the virus did not spread as widely.

Moss says he’s not overly concerned about distribution challenges, at least right now. Pfizer’s COVID-19 vaccine is one of many currently in development, and “I don’t have any reason to think this Pfzier vaccine is special in such a way that its efficacy is going to be substantially higher than another vaccine,” Moss says. (Time will tell, of course, exactly how the efficacy and availability of the different shots stack up.)

Many of the other vaccine candidates currently going through clinical trials do not have such stringent cold-storage requirements. Pharmaceutical companies Moderna, Johnson & Johnson and AstraZeneca have all said their COVID-19 vaccine candidates could be kept at temperatures of -20° C or above, which should make distribution easier.

Cannon adds that Pfizer and other vaccine makers may refine their formulas over time. Some other vaccines, such as those for measles and yellow fever, are shipped in a freeze-dried format and reconstituted with water before they’re administered. Something similar may be possible for COVID-19 vaccines in the future, Cannon says. The Pfizer spokesperson says the company hopes to release a COVID-19 vaccine that could be stored at temperatures between 2-8° C in 2022.

But for now, people should be prepared to wait awhile before life returns to normal. Even once vaccines are available, it will take time to achieve the widespread inoculation required to stop the virus from spreading unchecked. “I would say a best-case scenario may be toward the end of 2021,” Moss says. “But it’s going to depend on not just vaccine availability and approvals, but the willingness of people to accept the vaccine. There’s a whole other challenge and layer there.”

In the meantime, the best tools are the ones we’ve already got: social distancing, wearing masks and washing your hands.

The Wikipedia article on User:Tangerineheatwaves/Stay Grounded was added to the Aviation category.

The Wikipedia article on User:Tangerineheatwaves/Stay Grounded was added to the Aviation category.

In September 2017, two weeks after Hurricane Irma pummeled South Georgia, Angela Ammons found her hospital on life support. It was her first day as CEO of Clinch Memorial Hospital. As she walked the halls, past oversized framed photos of the nearby Okefenokee Swamp, she felt relieved that the hurricane had spared the facility, but overwhelmed by the growing list of longstanding problems, from broken equipment to low staff morale. Soon after, an auditor informed Ammons of the hospital’s ninth consecutive year in the red. The hospital had just enough cash to pay for a couple more days of operations. With only two of its 25 patient beds filled and little revenue coming in, Ammons didn’t know if she could make payroll. If nothing changed, she would be forced to close a hospital that had served the 6,650-person Clinch County, including the small town of Homerville, Georgia, for over six decades.

“Rural hospitals are an endangered species,” says Jimmy Lewis, CEO of Hometown Health, a professional association of four dozen rural Georgia hospitals. Clinch Memorial, he thought then, might become the state’s eighth shuttered rural hospital since 2010. Even before the coronavirus pandemic halted elective surgeries and the income streams they produce, rural areas had too few insured patients to sustain the hospitals built to serve them. But their empty beds could be of value, if linked up with city hospitals now facing a different problem: overcapacity, especially during COVID-19.

In 2017, Ammons didn’t know that just yet. She just knew she had to move fast.

Ammons had never before run a hospital. The daughter of a Korean immigrant and Vietnam War veteran, she was raised by her grandparents in Macon, Georgia. But their tumultuous relationship forced Ammons to flee home at age 15. She nearly became homeless, relying on the goodwill of people she hardly knew to offer temporary housing as she cobbled together shifts at Shoney’s. Ammons eventually became the first person on her mother’s side of the family to earn a college degree. For more than a decade, she climbed the ranks from doctor’s receptionist to registered nurse supervising a team. After the four previous CEOs failed at a turnaround, Ammons convinced Clinch Memorial’s board that her experience overcoming hardships would provide a fighting chance at reviving the hospital.

The rookie CEO froze salaries, cut costs and collected payment upfront for elective procedures. It wasn’t enough. “I was scared to death, and I needed help,” says Ammons, aware of the fact that closure would not only force residents to travel outside the county to the next-closest hospital, but also dig a knife deep into the heart of Homerville’s economy. “We had to do something different.”

Clinch Memorial faced the same problems beleaguering many of America’s roughly 2,000 rural hospitals, which serve 57 million Americans – a sixth of the nation’s population. The University of North Carolina’s rural health research program, which has tracked over 170 rural hospital closures since 2005, found last year was the worst year for closures since the Great Recession. Nearly a quarter of those left are near insolvency, according to a 2019 analysis from consulting firm Navigant. Many rural hospitals struggle because a majority of their patients are uninsured, and they often don’t get fully reimbursed for that care by the government. Obamacare gave states the option to cover some of those uninsured by expanding Medicaid: Georgia did not. Rural hospitals are closing at higher rates in such states, while rural areas in states that expanded Medicaid saw sharp declines in uninsured rates, according to a 2018 Georgetown University study.

In states that did not expand Medicaid, such as Texas, Georgia and North Carolina, the rural hospital crisis forced leaders to take extreme measures to save facilities that offer not just the only medical care in miles, but well-paying jobs. In 2014, the mayor of a small North Carolina town marched hundreds of miles to Washington D.C. in a long-shot bid to keep his hospital open. In 2017, the administrator of a Tennessee hospital launched a six-figure GoFundMe campaign to make payroll. Last year, an Oklahoma hospital’s staff kept working even after the paychecks stopped coming to keep the town afloat. Elsewhere, hospitals execs once fighting over patients are now collaborating with each other in finding ways to stay afloat. The devastating spread of COVID-19, leading to large outbreaks in rural nursing homes, meatpacking plants, and prisons, have amplified the need for these hospitals. It has also exacerbated the financial pressures many of those facilities already faced.

As Ammons desperately searched the Internet for answers in the fall of 2017, she stumbled upon a story about a hospital on the other side of Georgia. Two and a half hours west in Colquitt, a town even smaller than Homerville, a CEO seemed to have found an innovative approach that exploited an inefficiency within America’s bloated health care system. Now those hospital beds were full of patients from large southern cities, pumping new life into a hospital once in peril. Ammons didn’t fully understand how it worked, so she picked up the phone and dialed the 229 area code on the Miller County Hospital website.

When MCH CEO Robin Rau picked up, Ammons wasted no time asking for help. She sought mentorship from Rau on how to turn around Clinch Memorial. Rau could hear the desperation in Ammons’s voice. It resembled hers just a few years earlier.

A seasoned hospital administrator, Rau joined MCH just as the Great Recession started. At her first board meeting, Rau says, a lender called due a note worth over $3 million. Rau only had $100,000 in the hospital’s bank account. To cut losses, Rau tried a counterintuitive solution: offer free primary care to uninsured emergency department patients. Though the strategy required spending money upfront, it ultimately lowered expenses for patients who came to the emergency department with minor ailments. She then drove the more than 200 miles to Atlanta’s Grady Memorial Hospital, which was cutting costs during a financial crisis of its own. While the public hospital was overcrowded with patients, Rau’s beds were mostly empty. Rau convinced Grady to transfer uninsured patients who were intubated and required ongoing ventilation following car crashes, gunshot wounds, and traumatic brain injuries – but no longer needed intensive care – to MCH.

Grady benefitted because it could offload post-acute patients for which it received a lower reimbursement rate. In return, Rau could bill the federal government for offering care to patients in MCH’s once-empty beds. She could do this because MCH is a critical-access hospital – a classification that allows small hospitals located in remote areas to be eligible for federal reimbursement so long as they treat any patient regardless of their ability to pay. Under that designation, Rau could also “swing” her beds from only patients in need of acute care to those who no longer require the emergency department but still needed more treatment before a nursing home. Though many rural hospitals employed “swing beds,” Rau was one of the first to use it as a major revenue driver.

The strategy worked: Rau kept open her hospital’s doors, paid off debt and expanded services. But Rau felt wary about divulging her strategy to another CEO. Over a decade’s time, the hospital industry had grown fiercely competitive. Urban health systems not only expanded their patient services, but also increased their footprints into rural regions. Rau watched as larger systems rarely invested in their rural facilities. “I thought, ‘Is this going to end up being competition for me?’” Rau later told TIME. But sensing Clinch Memorial had nowhere else to turn, Rau agreed to help Ammons implement a swing bed program of her own.

They started talking by phone each week, slowly becoming familiar with each other’s hospital operations. When Rau drove to Homerville for a tour of Clinch Memorial, she was shocked and saddened by what she saw. “There were no patients, nobody coming in,“ Rau says. “It was like a daggum ghost town!” By the end of 2017, Rau’s swing bed program that treated intubated patients had a long waiting list. So she offered to send Clinch Memorial some of the patients who were already being transported hours from cities like Atlanta, Jacksonville, and Tallahassee.

One of those patients, Derry Wells from southwest Georgia and in her early 50s, had maxed out the days insurance would pay for her stay at a larger 181-bed hospital. She could no longer speak and required a ventilator due to a worsening rare neurological disorder called corticobasal degeneration. Before she could go to a nursing home, her husband, Randy Wells, a minister with the Church of God, was told about Rau’s program at MCH. Due to the waiting list, he agreed to send Derry to Clinch Memorial, where staffers helped her through a series of respiratory treatments and physical therapy.

“I’d never stopped in Homerville before,” says Randy Wells. “There’s something about small-town hospitals where they build a better rapport with patients and family members. It’s more personable.”

Founded by a doctor in the mid-19th century, the city of Homerville once bustled thanks to the railroad and, later, Clinch Memorial, built in 1957 with funding made available by the Hill-Burton Act, a 1946 law that provided hospitals federal grants and guaranteed loans for construction. But the growth of America’s highway system choked off life to many rural railroad towns. Homerville’s shrinking population—down 26% since 1980—slowly affected Clinch Memorial. When a new hospital was built in the mid-2000s, the board approved a new facility with only half the beds of the original site.

From 2007 to 2009, during the Great Recession, the number of nonelderly Americans without insurance increased from 45 million to 50 million, according to a 2010 analysis from health policy journal Health Affairs. As unemployment rose, Americans delayed pricey health care procedures and avoided hospital visits. Between 2008 and 2013, Clinch Memorial’s patient admissions had halved in spite of the fact that Clinch County, where Homerville is located, is home to some of Georgia’s worst rates of smoking, obesity and cardiovascular disease. Those outcomes, coupled with severe doctor shortages and a high percentage of uninsured residents, have contributed to the area’s life expectancy of 72.7, six years younger than the national average.

In the months following, as more ambulances dropped off ventilator patients, Clinch Memorial started showing signs of life. Ammons was relieved to see her daily census grow from two patients to six – some days, it even hit double digits. But the work was just beginning. As more out-of-town patients arrived in Homerville, and dollars flowed in from Medicare, she began to invest in the area’s longer-term needs by planning a wellness center, and programs that urged residents toward healthier lifestyles. Clinch Memorial was able to hire its first full-time staff physician in over five years.

Hopeful as she was, Ammons wasn’t ready to let her guard down. One day last summer, nearly two years after her first day as CEO, Ammons reflected on the hospital’s progress, but minced no words about the work still to be done to ensure its long-term vitality. “We’re not out of the woods,” she said.

As rural hospitals had spent years looking for ways to fill their empty beds, they experimented with a variety of solutions to draw in patients from outside their communities. So far, few hospitals have implemented the specific practice embraced by Ammons and Rau, according to Mark Holmes, director of the University of North Carolina’s Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research. But he says it fits into a broader trend of critical-access hospitals developing a specialty service line to “release the strain” from larger facilities. Small rural hospitals have increased the number of elective surgeries – knee or hip replacements, for instance – at a higher rate than other medical facilities. By developing that niche, rural hospital administrators are hoping to draw patients away from larger facilities.

“Could every critical-access hospital do [what Ammons and Rau are doing]? No.” Holmes said, noting that there are only so many excess patients to go around. But the broader concept “has the potential to work nationwide,” he said.

This past January, Ammons drove up for a meeting at MCH, bringing good news to share with Rau. Clinch Memorial was now in the black for the first time since the Great Recession. And Ammons’s “swing bed” program had grown nearly seven-fold from revenues of $730,000 in 2017 to over $5 million in 2019. During her visit, Ammons strategized with Rau, in hopes of furthering her turnaround effort. As they talked, Rau spoke freely about the progress she liked, offering constructive criticism wherever she saw fit. “Angela’s got good ideas, different ideas, some that I wouldn’t do just yet,” Rau said, referring to Ammons’s decision to offer holistic services such as spa or massage therapy. “I worry about her spreading herself too thin.”

By the time COVID-19 arrived in Georgia, Ammons was ready to respond. Clinch Memorial could now accept larger hospitals’ patients who were already on ventilators but didn’t have the infectious disease. At the beginning of the pandemic, the swing bed program drew in over $1 million in monthly revenues, which offset losses caused by the state’s temporary ban on elective procedures during its shutdown.

This past summer Georgia’s COVID-19 cases surged to record levels, so much so that hospitals were entirely full. So when Ammons learned a hospital in nearby Waycross had diverted patients, she offered to take some of their non-COVID-19 patients to free up space. They agreed. For the first time since Ammons arrived in Homerville, Clinch Memorial’s beds were now full, and patients who might’ve been left waiting for a bed at other hospitals got admitted sooner.

“I know that many are just trying to survive the day to day, but we can’t forget that we will get past this,” Ammons said. “This pandemic has inspired a lot of innovation that we will use for years to come.”