Lately, Doug Satzman’s AirPods have been running out of battery multiple times a day. Satzman is the CEO of XpresSpa, and like the leaders of businesses across the country, he had a rough spring as the COVID-19 pandemic spread across the U.S., shutting down cities in its wake. By March 15, Satzman had begun the process of furloughing the nearly 500 employees who work at the airport spa chain. With 46 locations in 23 airports in the U.S., XpresSpa is the spot you drop into for a quick massage during a long layover, or to freshen your manicure between flights. In other words, it’s a luxury — or in 2020 terms, a “non-essential.”

But even as the shops were shutting down and flight schedules were contracting, Satzman and the chairman of his board, Bruce Bernstein, decided to work toward a new — and newly critical — business model: COVID-19 testing. “As we were listening to the news, we’d hear about the need for testing, we’d hear about other countries doing this 30 days ago, we heard about South Korea curbing the spread in their communities with testing. We thought: is there a way we can reactivate our closed spas to at least temporarily turn them into COVID testing facilities and lend a hand to the efforts?” Satzman told TIME in mid-April. By then, he and Bernstein were making site visits to New York City’s JFK International Airport. In late May, they signed the contract to pilot their first testing program, planning to process about 500 tests a day for airport and airline employees. The location began testing its first patients on June 23, just as New York City reopened some restaurants and retail.

Getting even this single testing site up and running, which has been their singular focus for over two months — and the reason for all those dead AirPods, thanks to long hours logged on calls with legal teams, health partners and coworkers — has clarified the challenges that the U.S. faces in managing the coronavirus pandemic and its spread. “It’s not like you connect one dot to the next. It’s like you’re connecting one dot to the next with 16 puzzles at the same time, and trying to land in the same place,” Satzman says.

Evidence suggests that widespread testing for COVID-19 is the most critical factor in combating the virus’s spread, and a vital condition for fully reopening the economy. Countries like New Zealand and Iceland and cities like Hong Kong have effectively contained the virus thanks to aggressive mass-testing regimens, contact tracing and mandatory quarantines. But in the U.S., testing capabilities have been slow to ramp up, due to a mix of regulatory delays and confusion, supply limitations and still-evolving science. Pharmacies like CVS, Walgreens, Rite-Aid and Walmart took months to open only 69 drive-thru testing centers nationwide, though they’ve continued to slowly expand. As of June 13, over 27 million tests had been processed in the U.S. While that’s more than South Korea, for instance, the high rate of positive results in the U.S. — about 10% — reflects a testing bias towards those who are already ill or obviously exposed, likely because most tests in the U.S. were initially reserved for patients showing active coronavirus symptoms, often already in hospitals and emergency rooms. By mid-June, testing for the general public had increased dramatically to include free options for residents of Los Angeles, New York and other cities, including pop-up programs for participants in recent mass protests.

XpresSpa’s plan, however, is to serve a different customer, for a different purpose. It will be one of the first entities providing COVID-19 sampling facilities and test results to patients primarily at the bequest of on-site employers. In fact, if you’re sick, Satzman says, it’s preferable that you don’t come in. And for now, if you’re part of the general public, they’re not ready for you either. “This is meant to create a proactive testing process for those who probably don’t have symptoms but want to know they’re not contagious,” Satzman says. Instead, XpresSpa is building a blueprint for what happens after the crisis subsides and how to manage an industry’s health going forward.

In the U.S., air passenger traffic dropped about 95% in April; by mid-June, airports were still only seeing about 20% of the people they’d handled in the same time frame in 2019. Airport and airline employees — frontline essential workers with global exposure — are particularly vulnerable to potential infection, and spreading it. That’s where Satzman sees XpresSpa fitting in: it’s the leading health and wellness brand in airports globally, with prime real estate already set up in terminals at ports of entry across the country. Their labor force is TSA-approved with security clearance, which is a requirement for working in an airport. And since many massage therapists, manicurists and aestheticians receive disease-containment training as a requirement for their state licensing, they’re already one step further along the path towards providing a health-compliant testing environment than other independent entrants in the field — or at least, that was what Satzman and Bernstein figured in April.

Their focus is providing the services airport and airline employees need to stay operational. “One of the executives at JFK said their current protocol is that if someone calls out sick with symptoms, they have to send everybody [that person has] worked with home to stay quarantined for 14 days,” Satzman said in April, when the infection numbers were still climbing in New York. That remained true through June. “As soon as [the airline industry] starts picking back up, having 15 people at home for two weeks when one person had symptoms? It’s devastating. Now is the time to build this muscle for the workforce before the public starts returning.” In the days leading up to their opening, Satzman said some airline executives were counting on the new testing program. But as he’s discovered over the past three months, even eager clients, the right real estate and a licensed labor force are not enough to get a testing facility up and running quickly — despite the ongoing urgent need.

It’s past 10 p.m. on a Tuesday night, and Satzman is picking at his dinner after a late evening run in Central Park. It’s been a typically long day in the home office of his Upper West Side apartment, as a thunderstorm raged outside. First there was the daily 8 a.m. steering committee call with Bernstein; his newly-appointed medical director Dr. Lewis Lipsey, a New-York-based hematologist and oncologist; and a newly hired business consultant who would become their project lead, Calvin Courtney Knight. Then Satzman managed calls with three different legal companies, addressing New York state licensing and regulations, brand trademarking and HIPAA compliance, and two potential partners for electronic medical record management. There are brochures and website materials to develop, facility redesigns for medical treatment to oversee and job descriptions — phlebologists, nurse practitioners — to publicize.

And finally there is the COVID-19 test itself. Even after signing their agreement with JFK airport in early June, the XpresSpa team was still negotiating with final testing partners. They plan to offer the proven PCR nasal swab tests, likely processed at a local laboratory. They also eventually intend to offer the second type of test currently on the market, which measures antibodies in the blood. The first type of test diagnoses active infection; the second indicates previous infection. “It’s a moving target,” Satzman says. “Keeping up with the science has been the biggest hurdle.”

Initially, Satzman and his team had hoped to offer a minimally-invasive finger-prick test that returns results in minutes. By June, recognizing that testing locations around the country had struggled with faulty results using that test, they decided to go with the slower-turnaround but more proven blood draw procedure. There are about 100 antibody test options currently in the U.S. market, but only a few have FDA approval under an emergency authorization rule. Many have been subjects of recalls, or have been pulled from the market due to concerns about accuracy and processing. Early on, Satzman reached out to the first one out of the gate, Cellex. “Ironically, they didn’t have a test to sell,” Satzman recalled of their initial communication; they didn’t have a distributor and were still working on their production.

Dr. Anne Wyllie, an associate research scientist at the Yale School of Public Health who is working on a third type of COVID-19 test, says that, while frustrating, these roadblocks can be important to avoid rushing any science to market, especially as more retailers may turn to COVID-19 testing. “It can be dangerous to get things wrong at a time like this,” she says, expressing concerns about test sensitivity. In mid-May, the American Medical Association suggested that antibody tests should not be used to ascertain immunity or suggest an end to social distancing practices. Even months into the crisis, there remains little consensus around what widespread testing should look like that could clear buildings for occupation and maintain safe work environments for employees. In fact, some businesses are even planning to ask their own workers to sign liability waivers in case they catch COVID-19. Still, Wyllie sees XpresSpa’s plan as something with “potential.”

Before running XpresSpa, Satzman was a senior vice president of business development and retail operations at Starbucks. The world of health regulation and government bureaucracy is new to him, and filled with unexpected obstacles. “We have the real estate, we have money, we have willingness, smart people are working really hard a lot of hours — but it’s still slow and frustrating,” he says. Initially, XpresSpa looked to federal agencies like the CDC, HHS and FEMA for guidance, seeing their publicity in the news. But testing standards are actually set by each state, with varying regulations in every district. They discovered they would need to contract with a medical doctor or nurse practitioner for on-site management, while some lab work would also require them to meet Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) standards. Then they would need approvals from state health boards. “I think the federal government could take a more proactive role in assisting the testing efforts,” Satzman says. “What I’m seeing is states are figuring it out on their own, and they are figuring it out at different rates.” The result is inconsistencies that hamper speed. “When you have 50 different people trying to solve a similar problem…” he trails off. “It’s a built-in inefficiency. States want their own autonomy, but that’s one of the reasons we haven’t been able to get testing up and running.” The national patchwork of isolation rules and testing availability, which has continued well into the summer, reflects Satzman’s difficulties in getting a national program functioning quickly.

Airports themselves presented a second level of complexity: they are public entities, which means city councils and mayoral offices often control their operations. After the pilot program’s opening in JFK’s Terminal 4, Satzman hopes to expand to LaGuardia Airport and Newark Airport with the cooperation of the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. Atlanta’s Hartsfield-Jackson International Airport and Chicago’s O’Hare are also on the map with further locations to come, but timing remains up in the air. XpresSpa has made the most progress at JFK’s Terminal 4 because it is an unusual case: it’s operated by another private corporation. Plus, with New York as the virus’s epicenter in the U.S., it felt like the most pressing need when they began the process of putting the program together.

While working through the bureaucratic necessities, Satzman has reactivated some employees — a head of IT to help build out a new patient portal, his director of design and construction to retrofit their locations for use as testing centers, human resource managers to help with recruitment. On opening day, XpresSpa is bringing back some members of their preexisting work force that are interested, training them for specialized roles. But they also needed to hire new staff including lab technicians and healthcare roles — which meant they needed to work through TSA approvals for a new set of employees after all. Not that hiring itself is the issue. “A lot of the [potential new hires] want to get out of the hospitals,” Satzman says. “They are motivated to serve.”

Then there is the problem of procurement of personal protective equipment, or PPE: the sterile gowns, face masks and shields that U.S. facilities nationwide, including hospitals, have struggled to obtain. “We do have a line on supply, but one of the businesses we’ve talked to, their inventory level changes every few hours, not every few days,” Satzman said back in April. “It is a volatile supply chain.” By June, that hadn’t substantially changed.

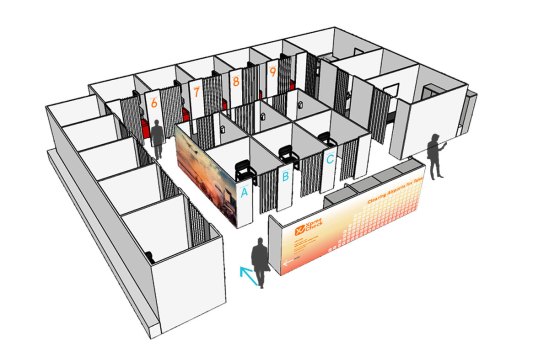

XpresSpa has four locations at JFK’s Terminal 4. Two of their biggest, one by Gate B24 and another next to a MAC Cosmetics shop, were initially prime contestants for the pilot program. But given the expected demand, the airport eventually offered 1,700 square feet of pre-security space in the Arrivals Hall for them to build out a temporary location, a modular structure of movable partitions with nine private testing rooms and six “intake” rooms, meaning there’s no communal waiting space. They expect to turn around an impressive 500 tests a day. “The beauty of an airport is you can operate long hours,” Satzman says, so they’re planning for multiple eight-hour shifts per day. In other airports, they may stick to converting preexisting real estate — but their spa and testing services, he stresses, will remain fully separate.

Satzman walks through the planned process: employers sign their work force up for testing, determining their own standards on who gets tested, and how often. Patients make appointments online and show up to a “frictionless” experience with no paperwork, shared clipboards or wait time in an enclosed space. By opening time, however, XpresSpa had decided to expand their service options to include walk-in testing for those with insurance, bypassing the employer. Either way, it’s insurance companies and employers who will likely foot the bill; by opening, it was still unclear where the buck would stop, however. “We are hopeful the federal government will cover it, but it’s unclear how testing facilities can seek reimbursement and how much the reimbursement is for. We’re not dependent on federal funding, but it would make things a lot more efficient once we learn the path,” Satzman says.

XpresSpa’s pivot to provide an essential service is not just altruistic: it’s smart business, capitalizing on preexisting resources and a $5.6 million loan through the Paycheck Protection Program in early May. But it also potentially positions them well in the public eye, presuming their efforts are successful. Like distilleries and fragrance manufacturers switching over to producing hand sanitizer, or fashion companies churning out masks, they’re just one company attempting to salvage both their operations and our collective situation. The result: as of the third week of June, XpresSpa’s stock price was up over 1,200% from its March low. And beyond mustering goodwill, their change of focus might reflect a meaningful new market position — or at least a roadmap to follow in future health crises.

For months, every night at 7 p.m., Satzman would stick his head out of his office window, face south towards the bright lights of Midtown’s office towers and join in with the city’s routine evening cheer for healthcare workers. Sometimes, he was on the phone with partners who could hear the yells through his AirPods. “They’re like, ‘Is that really happening?’ And I’m like, ‘Yep, that’s New York City, baby.’” Working from home — with his two school-age kids underfoot — has been an adjustment, just like for everyone else. But even as midnight neared and his dinner remained half-eaten, Satzman sounded energized. “Just like 9/11 impacted security protocol afterward, this pandemic is going to create some new health safety protocol in travel,” he envisions. Three months into the crisis, testing continues to be a hot topic, and the political appetite for it is only increasing: in late April, a congressional vote allocated $25 billion to testing, while National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease Director Anthony Fauci suggested the U.S. still needed to double testing before considering reopening the economy. In New York, Governor Andrew Cuomo signed an executive order in March enabling independent pharmacies to conduct tests for walk-in patients; the federal government followed suit with pharmacy authorization in early April. By June, however, pharmacists faced the same concerns about supply chain access and safety that have plagued XpresSpa, with little testing made available. The latest plan from the federal government, released May 25, places the onus on testing squarely on the shoulders of states, however, and suggested current testing levels would be sufficient.

But scientific opinion is firmly on the side of increased testing, even if the federal dollars are not. “Things are moving great. It’s just getting through the government hoops,” Satzman explained in late May, a touch wearily. By June, he was more optimistic: with the location contract in place, construction was kicking off in JFK and the road to testing was beginning to look clear at last. XpresSpa filed for a new trademark, XpresCheck, and Satzman was banking on opening before the end of June. And on June 22, he could be found handing out staff uniforms at JFK for the opening and submitting to the PCR swab test himself onsite. It won’t be quite the summer travel season they expected, but it’s a start. And if they succeed, it will be a new model of private-public partnership meant to get a grip on the pandemic’s impact while still putting health first.

No comments:

Post a Comment