By BY MARCUS WESTBERG from NYT Travel https://ift.tt/2ESGQKM

via IFTTT

The Wikipedia article on United Aviation Services was added to the Aviation category.

The Wikipedia article on United Aviation Services was added to the Aviation category.

It’s a very good time to be a domestic jet-setter on a budget. JetBlue’s fall sale, which took place in early August, featured tickets as low as $20 for trips between New York City and Detroit or Los Angeles to Las Vegas. Alaska Airlines recently offered a buy-one-get-one sale, a deal more familiar to Payless shoe shoppers than air travelers. United Airlines passengers could recently book themselves a round-trip from Newark, N,J. to Ft. Myers, Fla.—a major viral hotspot—for as little as $6, before taxes and fees hiked the price to a staggering—wait for it—$27. All of this, of course, assumes that you’re willing to risk exposure to COVID-19, a virus that has killed more than 170,000 Americans as of this week.

These deals exist because of a variety of reasons that have combined to send the U.S. aviation industry into bizarro mode. First and foremost, airlines are hurting badly. Air travel is down about 66%, judging by the number of people who passed through Transportation Security Administration checkpoints on Aug. 16 compared to the same number from a year prior; the four biggest U.S. airlines lost a combined $10 billion between April and June, the Associated Press reports.

Second, many airlines have only survived and avoided mass layoffs because they took pandemic-specific grants and loans from the federal government as part of the CARES Act, passed in March. Airlines that took that money are forbidden from mass layoffs until October; a fall bloodbath is likely.

Finally, the airlines that took those loans also agreed to maintain a certain level of service regardless of passenger demand, and carriers figure that if they have to fly some routes anyway, they might as well try to make some money in the process, even if it’s just $6. (The government has since relaxed at least some of those service requirements.)

Airlines across the U.S. have made a big deal of what they’re doing to keep individual passengers safe while aboard their aircraft. All the major carriers require passengers to wear masks, some aren’t selling middle seats, and they are cleaning more thoroughly and more often. And at least some experts say it’s safe for individuals to fly without fear of contracting COVID-19 on an airplane, in part because cabin air is continually refreshed (that said, many epidemiologists say they, personally, don’t feel comfortable taking the risk of flying right now).

But so far, the U.S. aviation industry has said little about the macro-level threat of people spreading the virus around the country via air travel—the business of offering cheap tickets during a global pandemic is one thing, the ethics are another. COVID-19 came to the U.S. on airplanes, and the global viral picture would surely look different if it weren’t for modern air travel, which lets a person reach San Francisco or Seattle from Wuhan, China in the blink of an eye relative to, say, a steamship.

“The chance that any specific individual who boards a plane is sat next to an infected host and contracts the virus is low,” says Dr. Robin Thompson, a mathematical epidemiologist at Oxford University who has researched air travel’s role in viral outbreaks. “However, when many individuals travel, the probability that some infections occur—and the risk that the virus is transported between countries by any of those individuals—is no longer negligible.”

Similarly, the ability to fly from one corner of the U.S. to another in mere hours is also a public health threat, as travelers can unknowingly bring the virus from hotspots to areas where it’s more under control, potentially sparking a new outbreak. An Aug. 18 ProPublica report based on anonymized location data found that, of 26,000 smartphones identified on the Las Vegas strip in a four-day period in mid-July, some of those same devices were later spotted in every contiguous U.S. state but Hawaii, underscoring air travel’s unique capability to spread people—and thus a contagion like COVID-19—around the country at great speed and ease.

It’s too early to say for sure how air travel is fueling domestic viral spread in the U.S. relative to other methods of transportation. But states near one another tend to have similar COVID-19 situations, meaning the risk of an infected person sparking a new outbreak by driving to a neighboring state is probably much lower than the risk of doing so by that person flying across the country.

Meanwhile, while U.S. airlines are offering round-trip flights to viral hotspots for less than the cost of an Uber to the airport, foreign carriers are dramatically reducing service to cities with known outbreaks—flights to Auckland, New Zealand, for instance, were scaled back in mid-August after a new outbreak there of fewer than 100 cases. “This U.S. government, unlike governments around the world, has basically set it up so that airlines, and most other businesses, are engaged in a free-for-all,” says Brian Sumers, senior aviation business editor at Skift, a travel industry news site. “It’s all about the economy, and nobody’s thinking about the social or ethical ramifications of decisions about airline capacity.”

Absent government requirements to do so, it’s unreasonable to expect U.S. airlines to trim their service in the interest of public health. They are corporate enterprises beholden to shareholders, and while it makes good business sense for them to focus on individual passenger safety to convince people it’s safe for them to fly again, there’s little incentive for them to care all that much about big-picture public health. The airlines are fighting for their lives, after all, and it’s important to keep in mind that they support at least 10 million jobs, according to Airlines for America, a trade group. “Their businesses have been decimated, they’re just trying to survive, they have all these airplanes, they want to make some money, and if the best way that they can make a little bit of money is to offer $27 round-trip fares to Florida, they’re going to do it,” says Sumers. Furthermore, the CARES Act’s service requirements were set early in the U.S. outbreak. The viral landscape has changed since then, and, in some cases, airlines are more or less mandated to fly to what have since become viral hotspots.

But what is reasonable is for airlines to rethink the wisdom of offering cheap-as-chips flights during a deadly pandemic that shows few signs of ebbing. Moreover, the U.S. aviation industry, which has gotten only limited pandemic guidance from the federal government, “needs some kind of safe-travel protocol,” says Henry Harteveldt, a travel industry analyst and president of Atmosphere Research Group. He points to countries like France, which is requiring inbound international passengers to be tested for COVID-19.

Of course, mass passenger testing is harder to do for domestic U.S. travelers, given their sheer volume; nearly 800 million people flew within the U.S. in 2018, compared to just over 200 million international passengers. And like so many other problems presented by the pandemic, this one, too, comes back to testing—with delays mounting across the country and results all but useless by the time they arrive, there’s simply no way to ensure that everybody getting on board an airplane right now is truly free of the virus. Many U.S. airlines are requiring passengers to self-certify their health, but there’s no guarantee people will be honest about their condition.

“As long as people are not required to prove that they’re in good health before they travel, there’s a risk that someone could get on a plane, and perhaps not infect anybody on that plane, but infect somebody at the destination,” says Harteveldt.

The Wikipedia article on Formation Light was added to the Aviation category.

The Wikipedia article on Formation Light was added to the Aviation category.

Travel curbs and border restrictions are upending lives around the globe, with some people resorting to chartering planes on their own or paying many times the regular ticket price to get back to their jobs and homes.

Eight months into the pandemic, the push to normalize is seeing some try to travel internationally again, whether for a long-delayed but essential business trip or to return to where they live. Yet with global coronavirus cases surpassing 18 million and rising, airlines are only reluctantly adding flights to their bare-bones schedules, and virus resurgences have some countries imposing new travel rules.

The flight paralysis underscores how deep and lasting the pandemic’s damage is proving to be. The number of international flights to the U.S., Australia and Japan has fallen more than 80% from a year ago, while flights to China are down by more than 94%, according to aviation industry database Cirium.

Travelers have to be creative just to get on a plane. Support groups have sprung up on Facebook and Wechat for those who have been stuck thousands of miles from their jobs, homes and families. Unable to get tickets, some are attempting to organize private chartered flights, while travel agents say they’re having to bribe airlines for limited seats. Others are shelling out for business or first-class tickets, only to be turned away for lack of the right documentation.

“So many people with families are separated, it’s so heart-breaking,” said Ariel Lee, a mother in Shanghai who administers a few Wechat groups of 1,650 members in total trying to get into China. “The toughest part is there are no clear guidelines and there’s no end date to this.”

The hopeful talk of travel corridors and a summer recovery have faded away among airline industry experts, replaced by a consensus that global travel will not effectively re-start before a vaccine is found.

“We are not going to see a material recovery for international travel in the near future,” said Steven Kwok, associate partner of OC&C Strategy Consultants Ltd. “The pandemic also brings about a consequential impact beyond the virus outbreak –- it is causing a slowdown in the global economy, which will hurt travel appetite for a longer term.”

Chris Wells had been stuck in his hometown in Texas for half a year, eagerly looking to return to Guangzhou, a city in southern China where he’s been living and working for more than a decade. International travel to China has been severely limited by the government to stem imported infections, and any seats on flights are snatched up almost instantly.

Wells, 41, a manager in an international sourcing company, searched and searched for a ticket. The only one he could find: an $8,800 one-way, first-class flight from Chicago to Shanghai, via Zurich.

“It was the only seat available,” he said. “I’d normally never pay that much for a ticket, but I was desperate to get back so I grabbed the seat when I found it.”

Cherry Lin, a Shanghai-based travel agent, said her company is having to pay kickbacks to airlines — more than 10,000 yuan ($1,438) per seat — to get tickets on popular routes like those departing from the U.S. and U.K. that they can then sell to customers.

The flight or passenger cap set by many countries largely limits seats, pushing fares up — a ticket for a direct flight from London to Shanghai is currently going for about $5,000, said Lin, but those are quickly purchased.

Additional seats are likely to pop up this month as more airlines resume flights, “but still not enough that everyone can easily buy online,” she said.

Jessica Cutrera, 44, an American who has lived in Hong Kong for more than a decade, was looking to return to the Asian financial center last month when the city suddenly required a negative virus test for passengers coming from high-risk countries including the U.S. She had to show results from a test taken within 72 hours before boarding and fulfill a requirement that travelers present a letter — signed by a government official — verifying that the lab is accredited.

Getting test results within 72 hours was hard enough given that testing is so backed up in the U.S that results usually aren’t available before a week. Then there was the required letter. “I called everybody I could find,” she said. “Most offices and agencies said no, it didn’t make sense to them to sign such a letter.”

Eventually, someone in California agreed to sign. So Cutrera flew from Louisville, Kentucky, to Chicago, and then to Los Angeles, where she had the test done. A few days later, she was allowed to board her flight to Hong Kong, while others trying to get on the same plane were turned away as they didn’t have the proper paperwork.

Cutrera is proving to be one of the lucky ones, as many continue to be in limbo.

Lucy Parakhina, a 33-year-old Australian photographer, had decided to stay in London, where she has lived for two years.

But in June, she started to plan a return trip when her U.K. work visa expired. Though she managed to buy a one-way ticket from London to Sydney for less than 700 pounds ($922) with Qatar Airways, she was bumped from her flight and told it was postponed.

She already left her job in London and gave up her apartment, and won’t have income to stay in the U.K. beyond September. But with a virus resurgence in Australia showing no signs of ebbing and international flights down by 92% to the country, she’s likely stuck for a while.

“Now the only thing I can do is to wait for the easing policies and my flight to depart as planned,” she said.

In a small room without windows, I am instructed to breathe in sync with a colorful bar on a screen in front of me. Six counts in. Six counts out. Electrodes tie me to a machine whirring on the table. My hands and feet are bare, wiped clean and placed atop silver boards. My finger is pinched by an oximeter, my left arm squeezed by a blood-pressure cuff. Across from me, a woman with a high ponytail, scrublike attire and soft eyes smiles encouragingly. She is not a doctor, and this is not a lab. The air smells like lavender and another fruity scent I later learn is cassis. My chair is made of woven reeds, topped with a thick cushion and a pillow for lumbar support. The windowless room feels more cozy than claustrophobic; this is not torture but a luxury. I am, in fact, in a five-star resort with a 2,000-sq-m spa and an indoor heated pool. This process, I have been promised, will help me sleep better.

For years, I had been waking up exhausted. My primary care doctor ran my blood work three separate times to try to suss out an underlying problem, and each time it came back fine. I had no problem falling asleep, or even really staying asleep. The problem was that no matter how many hours of sleep I got, I had to haul myself out of bed in the morning, grumpy and lethargic.

So, in December, before COVID-19 ravaged the world and made travel unsafe, I journeyed to a beautiful valley in Portugal’s Port wine region to take part in the €220-per-night Six Senses Sleep Retreat to try to learn to sleep better. Six Senses has long made wellness and sustainability two of its main pillars of business. They have yoga retreats and infrared spas. They’re aiming to be plastic-free by 2022—all plastic, not just single-use. But for the past two years, the luxury resort brand has bet big on sleep. In 2017, they launched a sleep program with a sleep coach, sleep monitoring, a wellness screening, bedtime tea service and a goody bag of sleep-health supplies. The idea was that, with three nights of analysis and behavioral adjustments, I might finally train my body to get a good night’s sleep. It’s a vacation with a purpose, and it’s one with big appeal: Six Senses offers the program at 10 of its resorts and is requiring all new resorts (including New York City in 2021) to include the program.

Luxury hotels have been pushing health as a selling point for travel since well before events made the two oxymoronic. The global wellness-tourism market was valued at $683.3 billion in 2018 by Grand View Research, and according to the Global Wellness Institute’s 2018 report, 830 million wellness trips were taken by travelers in 2017. That was up nearly 17% from 2015. In 2018, American Airlines partnered with the meditation app Calm to help their passengers sleep. Headspace has partnerships with seven different airlines to do the same thing, all over the past few years. A survey from the National Institutes of Health shows that the number of U.S. adults who reported meditating while traveling tripled from 2012 through 2017. And all this travel wellness has one common goal: to get people to sleep better, because we know that—generally—people aren’t sleeping well.

In 2016, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) published findings claiming that one-third of adults are not getting enough sleep and that sleep deprivation is costing the country some $400 billion each year in productivity. It is also important to note that many studies have found a large disparity in sleep quality based on race, ethnicity and socio-economic status. In comparisons of white and Black populations, studies have found that white women have the best sleep duration and Black men the worst. Those disparities do not go away when studies adjust for socio-economic level. The Sleep Foundation writes that a factor may be higher levels of stress because of discrimination in daily life.

Although consumers have opened their wallets in pursuit of better sleep since the debut of memory foam in 1966, the past five years have been a boom for the sleep-wellness industry. The global sleeping-products market brought in $69.5 billion in revenue in 2017, and, according to the most recent report published in May 2018 by P&S Market Research, the industry is on track to hit $101.9 billion in 2023. The consulting group McKinsey put out a seven-page guide to investing in sleep health in 2017. And anyone who has tried to buy a mattress online recently has noticed just how many new mattress brands there are: Casper, Tuft & Needle, Purple, Leesa, Allswell, SleepChoices, Bear. The U.S. mattress industry has doubled in value since 2015, from $8 billion to $16 billion.

In my desperate quest for good sleep, I’ve bought into all of this. When I sat down to calculate it all, I was stunned to find that over the past three years, I have spent more than $1,000 on sleep. I bought a Fitbit, a Sonos speaker with a built-in alarm, a new pillow, a new mattress, a fluffier comforter, a weighted blanket, cold eye masks, a humidifier, pajamas made of bamboo, pajamas made of 100% cotton, pajamas made of satin and an alarm clock that mimics a sunrise. The sleep retreat, I hoped, would do something all the other purchases had not.

I don’t sleep well on the plane. After four hours of fitful slumber interrupted by turbulence, dinner service and my seat neighbor bumping into me on the red-eye from New York City to Lisbon, I groggily deplane and replane for the short flight to Porto, down another espresso and drive the one and a half hours to the Douro Valley. By the time I arrive at the hotel, the sun is beginning to set and my bed looks very inviting. It is only 5 p.m.

I’m led to my room by a woman named Vera who introduces my supplies: an eye mask, bamboo pajamas, earplugs, lavender spray for my bed and a worry journal where I can write down anything bothering me before I sleep. I flop down on the €2,500 mattress and hope that whatever I learn here will be easily transferable to the $200 mattress I bought off Amazon and my sad cotton-blend sheets. By the bed is a small box made by ResMed, which will track my movements while I sleep and present me with colorful graphs of data each morning.

I follow the given instructions: eat dinner leisurely, have only one glass of wine, take a bath in the deep tub, drink chamomile tea, put on the new pajamas, write in the journal and go to bed around 10 p.m. When I wake up, the ResMed app shows a series of colorful bars—my “sleep architecture” progression through deep, REM and light sleep—and a score of 97. “I had nothing to say about that sleep,” shrugs Javier Suarez, the director of the spa and wellness programs at Douro Valley, at my first consultation. He studied physiotherapy at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), and he knows this is abnormally good. “What we [often] see here is the first night, [guests] sleep bad because they come jet-lagged or they’re anxious,” he says. I’d slept a hard, uninterrupted eight hours. I feel proud of the prep I did before I came, adjusting my bedtime to try to prevent jet lag.

There are many scientific reasons to desire good sleep. Poor sleep quality is associated with a whole host of unhealthy side effects. Getting bad sleep puts people at a higher risk for diabetes, cardiovascular disease, Alzheimer’s, impaired memory, problem-solving issues, fatigue, anxiety, mood disturbances and poor performance at work. There’s a market, then, to help people sleep better, not just because it makes money, but also because it is generally good for people. “There’s no wellness without good sleep. Forget about it,” Suarez tells me. “If you don’t make sleep your priority, then you will not be healthy.”

The Global Wellness Institute attributes the growing wellness industry to four things: an aging population, increased global rates of chronic disease and stress, the negative health impacts of environmental degradation and the frequent failures of modern Western medicine. In the case of insomniacs, the ever popular sleep drugs Ambien, Lunesta, Sonata and others received black-box warnings from the FDA—the agency’s most serious caution—in May 2019. Those turned off by the foreboding -packaging may turn to more holistic sleep-wellness methods. Sleep scientists have also been working to better publicize their research on the benefits of sleep hygiene. In 2013, the CDC and the American Academy of Sleep Medicine launched the National Healthy Sleep Awareness Project, which aimed to raise public knowledge of sleep disorders and the ways sleep affects health.

Obsession is the inevitable peak of any trend. While I’m at the resort, Suarez recommends several other ways I can optimize my health, including Wellness FX, a company that will run a full blood panel, and Viome, a company you can mail your poop to in order to learn about your gut -micro-biome. We have the ability now to analyze absolutely -everything about ourselves sans doctor oversight: our blood pressure, our pH, our urine, our poop, our genes. Sleep is just part of the cultural movement toward health obsession. A 2017 study done by Rebecca Robbins at New York University found that a full 28.2% of people in the U.S. track their sleep—with an app, a wearable sleep tracker, or both—and Robbins, now a postdoctoral fellow at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, says she thinks that number has likely increased since the study.

All this data is what runs the sleep-wellness industry. Every major sleep-wellness company tracking sleep is collecting data—cumulative data. Eight Sleep, for example, says it has 40 million hours of sleep traffic logged. Alexandra Zatarain, a co-founder and vice president of brand and marketing for the company, says the medical establishment has “never had access to people’s actual sleep [outside of] clinical settings.” Six Senses, on the other hand, has complete data about how people sleep when they’re on vacation, thanks to their sleep programs. Companies theoretically use all this data to make their products better for the consumer, but they also use it for targeted marketing (perhaps to sell you a new pillow or blanket) or sell it outright. Some sleep-wellness companies more benevolently share their data with academic institutions to learn more about what it could mean. Eight Sleep is working on studies with Mount Sinai, UCSF and Stanford. Matt Mundt, who founded a company called Hatch Sleep, which makes a blanket cocoon sleep pod for adults, says he plans to announce a partnership with a major medical system to bring the product into clinical trials.

The sleep-wellness industry is made up of three categories of products: treatments (prescription sleep aids, homeopathic remedies, and doctor interventions like surgeries or sleep-apnea-treatment devices), routine disrupters (sleep trackers, meditation apps, dietary changes and sleep programs) and nesting (mattresses, pillows, curtains, humidifiers). Treatments are mainly performed and monetized by the medical industry and the hospitality industry (like this sleep retreat). Most of the buzzy sleep-wellness companies like Eight Sleep, Oura, Casper and OMI are creating products that fit into the routine disrupter and nesting categories. Eight Sleep, for example, sells a mattress that regulates its own temperature (nesting) and tracks your sleep to provide personalized coaching (treatment). The brand has raised $70 million over the past three years, with $40 million of that raised in November. Zatarain says the company plays to the public desire to self-analyze and self-optimize. “We want people to be asking themselves, ‘Am I sleep-fit, or not?’” she says.

After my first night of delicious, wonderful 97-score sleep, I’m feeling a little cocky. I—I’ve convinced myself already—am sleep-fit. Suarez is not so sure. “I bet you tonight you’re going to do worse,” he says on day two. “You’ll get an 87 or something.” The data, he says, does not care about my confidence.

I spend much of my second day at the retreat thinking about my sleep score. The keys to good sleep, I’m told, are simple: exercise; eating well; not drinking too much; a dark, quiet space; creating a wind-down routine; no screens two hours before bed; and a comfortable bed. The greatest enemy of sleep is stress. The main value of the sleep score—and sleep tracking in general—is not to affect your sleep, but to tell you when you need to change your waking habits.

“The biggest win [of sleep tracking] is in the behavior change,” says Els van der Helm, the co-founder and CEO of Shleep, which designs customized sleep programs. Through her company, van der Helm works to convince companies that employees’ sleep should be prioritized not only because it is good for them, but also because it will make the company more profitable. (Shleep itself raised $1.4 million in venture capital in August 2019.) At her presentations, van der Helm sees the same behavior again and again. As she describes easy things employees can do to improve their sleep, she suggests a wake-up light alarm. Immediately, everyone grabs their phones and orders one online. “That’s great, but can they be as passionate about exercise, or creating a wind-down routine?” she says. “The issue is that people love throwing money at the problem and just buy something and think they’re good. ”

The problems with our sleep—for those who are otherwise healthy—are often problems we can fix ourselves. “You don’t need any of that stuff,” Suarez tells me when I run through the list of products I’ve tried. “People say, ‘How can I sleep better?’ And my answer is, ‘How can you have a better life?’”

Making sleep improvement all about what we can purchase to help us also creates an untrue narrative around what that data means. In her study on sleep-tracking habits, Robbins also found a disparity in who tracks their sleep: the higher a person’s income, the more likely they were to track their sleep. “A very concerning aspect of the conversation around sleep is the message that sleep is a luxury,” Robbins says. “We need to remove the notion that sleep is a luxury and replace it with the truth, which is that sleep is something we all deserve and that unifies us.”

So on my second day at the sleep retreat—yes, a massive luxury—I do everything right. I think about my sleep score and forgo a second glass of wine, even though I’m on vacation. I think about my sleep score and go to yoga. My body and I deserve it.

That night, I feel terrible getting into bed. I’m stressed about the amount of work I have to do, and I keep thinking about how that stress will disrupt my sleep. Suarez is either a sleep witch who intentionally cursed me, or someone who knows what he’s talking about. My money is on the latter. I close my eyes and open them again only a few hours later, thinking about my sleep score. Eventually, I get back to sleep and wake in the morning to a markedly worse 85.

Suarez had warned me that some Type A people slept worse on their second night simply because they knew they were being tracked, but when Vera reviews my Night 2 results, she says she can tell what the problem was. The ResMed shows two scores for each night’s sleep, both calculated based on your movement in bed: one for your mental sleep and one for your physical. On the second night, my mental sleep was fine. It was my body sleep that was a disaster. I needed, Suarez says, to wear myself out.

On the third day, I sign up for a cardio class in the gym after a nice long walk. By the time I begin my wind-down routine in the evening, I’m already sore. In the morning, I wake up feeling refreshed. I can’t remember the last time I felt this way first thing in the morning. I roll over and check my score: 94. Success. The charts show that I had not only slept well, but I also got plenty of deep sleep. “I’m not giving you a perfect solution for sleep,” Suarez says before I leave the resort, “I’m just showing you what happens when you do things right.”

When I return from the sleep program, I feel better physically than I have in a long time. I find myself making decisions based not on my health, but on how they will affect my sleep quality. I don’t have coffee late even though it’s a struggle to stay awake back on the East Coast. I do my wind-down routine and spray my lavender spray and sleep hard through the night. The biggest change, though, is how often I think about my sleep, which is constantly. I join a gym, something I had been meaning to do for a year, simply because I know it will help me sleep. And it does work—for a while.

My perfect sleep routine begins to devolve even before the pandemic hits. At home, I fall asleep with the TV on watching Monday Night Football. I don’t have time to exercise every day. Unsurprisingly, I’m much, much more stressed than I had been at the luxury hotel with every amenity in the world and no job to do. I need motivation—inspiration—so I turn to Instagram, and I find @followthenap.

Alex Shannon is a “sleep influencer” who spends most of his time running the account, crafting cozy-looking images of heavenly sleepscapes. He started the account a year and a half ago and says he has noticed a substantial growth in the focus on sleep health in the time since. The boom in products has been good for him too. Every new supplement or sunrise alarm clock or mattress is another potential sponsorship. He’s one of only a few influencers focused solely on sleep, but plenty of general wellness influencers also dabble in sleep, and the content is there. More than 26.8 million posts on Instagram have been tagged #sleep and almost 4 million have been tagged #nap. Even now, when he’s not traveling because of COVID-19 concerns—he was often sent to expensive sleep retreats gratis, in exchange for posts—Shannon has pivoted his sleep content to his own home. And he says he’s had a lot of interest from foreign travel boards making plans for when the travel restrictions are lifted. “I feel like as recently as a few years ago, making rest and relaxation a priority was seen as selfish somehow,” Shannon says, “but with the rise of ‘self-care,’ it’s become much more acceptable to slow down and take care of ourselves.”

Part of that impulse to slow down has been engineered by sleep companies themselves. If wellness can look good on Instagram, it can make money. Just take the boom in Casper sales. Casper was hardly the first mattress startup to market, and it wasn’t even the first to roll its mattresses. But in 2014, the company encouraged customers to post videos unboxing their Casper mattresses and watching them unfurl. The influx of mesmerizing videos, all featuring Casper’s logo, helped the company become the leading brand in mattress startups. James Newell, a vice president at an investment firm that backed Casper, said in an interview with Freakonomics that Casper “would tell you they’re not a mattress company, they’re a digital-first brand around sleep.” It helps that Casper is estimated to have an $80 million marketing budget.

“Our brand ambassadors”—a common synonym for influencers paid to promote a product—“are providing their honest feedback and review of our products, providing potential customers with another perspective outside of our own,” says Julianne Kiider, the affiliate and influencer manager for Tuft & Needle. “The way we sleep is such a personal thing, so these diverse perspectives help guide followers to the right product for their own sleeping habits.” Several major mattress brands declined to share data about how much of their advertiser budgets are spent on influencers, if mattresses are given to influencers for free, and how well influencer marketing really works. But a scroll through major wellness-influencer accounts shows plenty of cozy bed photos with discount codes in the captions. Shannon says in this scenario, the influencer’s payment is often a kickback of the percentage of mattresses sold with their discount code. For him, it’s paying off.

“We all dream of being a little more relaxed, a little less stressed and not feeling guilty about indulging ourselves,” he says. That dream—of sleeping through the night and being more relaxed and waking up refreshed and ready for the day—is exactly what has made sleep wellness such a lucrative industry.

In March, four months after my visit to the sleep retreat, COVID-19 began to spread in the U.S., and the dream felt further away than ever. Several of my friends got sick, and I stopped sleeping. Then the Black Lives Matter protests began, and I continued to sleep fitfully, worried for my friends and fellow citizens. This time, though, I knew what mistakes I was making. I knew that stress was keeping me awake, bolstered by scrolling through my phone for news updates until 11 p.m. and not exercising and having another glass of wine. I knew all that, but I was too stressed to stop. One night, in a sleepless haze, I swiped away from the news and found myself browsing my old online shopping haunts. I added a new lavender spray and a set of pajamas to my cart, and clicked Buy Now.

McKinney is a features writer and co-owner at Defector Media

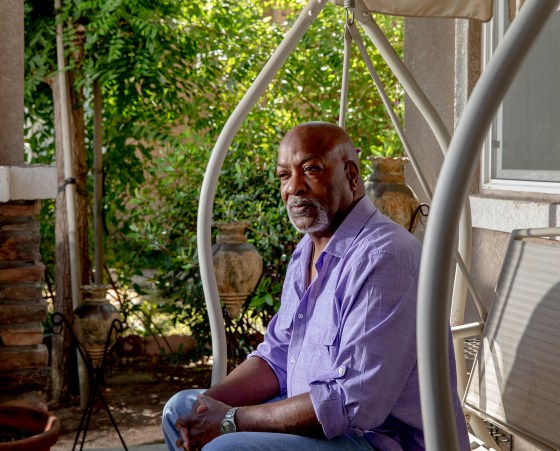

For 23 years, Larry Collins worked in a booth on the Carquinez Bridge in the San Francisco Bay Area, collecting tolls. The fare changed over time, from a few bucks to $6, but the basics of the job stayed the same: Collins would make change, answer questions, give directions and greet commuters. “Sometimes, you’re the first person that people see in the morning,” says Collins, “and that human interaction can spark a lot of conversation.”

But one day in mid-March, as confirmed cases of the coronavirus were skyrocketing, Collins’ supervisor called and told him not to come into work the next day. The tollbooths were closing to protect the health of drivers and of toll collectors. Going forward, drivers would pay bridge tolls automatically via FasTrak tags mounted on their windshields or would receive bills sent to the address linked to their license plate. Collins’ job was disappearing, as were the jobs of around 185 other toll collectors at bridges in Northern California, all to be replaced by technology.

Machines have made jobs obsolete for centuries. The spinning jenny replaced weavers, buttons displaced elevator operators, and the Internet drove travel agencies out of business. One study estimates that about 400,000 jobs were lost to automation in U.S. factories from 1990 to 2007. But the drive to replace humans with machinery is accelerating as companies struggle to avoid workplace infections of COVID-19 and to keep operating costs low. The U.S. shed around 40 million jobs at the peak of the pandemic, and while some have come back, some will never return. One group of economists estimates that 42% of the jobs lost are gone forever.

This replacement of humans with machines may pick up more speed in coming months as companies move from survival mode to figuring out how to operate while the pandemic drags on. Robots could replace as many as 2 million more workers in manufacturing alone by 2025, according to a recent paper by economists at MIT and Boston University. “This pandemic has created a very strong incentive to automate the work of human beings,” says Daniel Susskind, a fellow in economics at Balliol College, University of Oxford, and the author of A World Without Work: Technology, Automation and How We Should Respond. “Machines don’t fall ill, they don’t need to isolate to protect peers, they don’t need to take time off work.”

As with so much of the pandemic, this new wave of automation will be harder on people of color like Collins, who is Black, and on low-wage workers. Many Black and Latino Americans are cashiers, food-service employees and customer-service representatives, which are among the 15 jobs most threatened by automation, according to McKinsey. Even before the pandemic, the global consulting company estimated that automation could displace 132,000 Black workers in the U.S. by 2030.

The deployment of robots as a response to the coronavirus was rapid. They were suddenly cleaning floors at airports and taking people’s temperatures. Hospitals and universities deployed Sally, a salad-making robot created by tech company Chowbotics, to replace dining-hall employees; malls and stadiums bought Knightscope security-guard robots to patrol empty real estate; companies that manufacture in-demand supplies like hospital beds and cotton swabs turned to industrial robot supplier Yaskawa America to help increase production.

Companies closed call centers employing human customer-service agents and turned to chatbots created by technology company LivePerson or to AI platform Watson Assistant. “I really think this is a new normal–the pandemic accelerated what was going to happen anyway,” says Rob Thomas, senior vice president of cloud and data platform at IBM, which deploys Watson. Roughly 100 new clients started using the software from March to June.

In theory, automation and artificial intelligence should free humans from dangerous or boring tasks so they can take on more intellectually stimulating assignments, making companies more productive and raising worker wages. And in the past, technology was deployed piecemeal, giving employees time to transition into new roles. Those who lost jobs could seek retraining, perhaps using severance pay or unemployment benefits to find work in another field. This time the change was abrupt as employers, worried about COVID-19 or under sudden lockdown orders, rushed to replace workers with machines or software. There was no time to retrain. Companies worried about their bottom line cut workers loose instead, and these workers were left on their own to find ways of mastering new skills. They found few options.

In the past, the U.S. responded to technological change by investing in education. When automation fundamentally changed farm jobs in the late 1800s and the 1900s, states expanded access to public schools. Access to college expanded after World War II with the GI Bill, which sent 7.8 million veterans to school from 1944 to 1956. But since then, U.S. investment in education has stalled, putting the burden on workers to pay for it themselves. And the idea of education in the U.S. still focuses on college for young workers rather than on retraining employees. The country spends 0.1% of GDP to help workers navigate job transitions, less than half what it spent 30 years ago.

“The real automation problem isn’t so much a robot apocalypse,” says Mark Muro, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution. “It is business as usual of people needing to get retraining, and they really can’t get it in an accessible, efficient, well-informed, data-driven way.”

This means that tens of thousands of Americans who lost jobs during the pandemic may be unemployed for years or, in Collins’ case, for good. Though he has access to retraining funding through his union contract, “I’m too old to think about doing some other job,” says Collins, who is 63 and planning on taking early retirement. “I just want to go back to what I was doing.”

Check into a hotel today, and a mechanical butler designed by robotics company Savioke might roll down the hall to deliver towels and toothbrushes. (“No tip required,” Savioke notes on its website.) Robots have been deployed during the pandemic to meet guests at their rooms with newly disinfected keys. A bricklaying robot can lay more than 3,000 bricks in an eight-hour shift, up to 10 times what a human can do. Robots can plant seeds and harvest crops, separate breastbones and carcasses in slaughterhouses, pack pallets of food in processing facilities.

That doesn’t mean they’re taking everyone’s jobs. For centuries, humans from weavers to mill workers have worried that advances in technology would create a world without work, and that’s never proved true. ATMs did not immediately decrease the number of bank tellers, for instance. They actually led to more teller jobs as consumers, lured by the convenience of cash machines, began visiting banks more often. Banks opened more branches and hired tellers to handle tasks that are beyond the capacity of ATMs. Without technological advancement, much of the American workforce would be toiling away on farms, which accounted for 31% of U.S. jobs in 1910 and now account for less than 1%.

But in the past, when automation eliminated jobs, companies created new ones to meet their needs. Manufacturers that were able to produce more goods using machines, for example, needed clerks to ship the goods and marketers to reach additional customers.

Now, as automation lets companies do more with fewer people, successful companies don’t need as many workers. The most valuable company in the U.S. in 1964, AT&T, had 758,611 employees; the most valuable company today, Apple, has around 137,000 employees. Though today’s big companies make billions of dollars, they share that income with fewer employees, and more of their profit goes to shareholders. “Look at the business model of Google, Facebook, Netflix. They’re not in the business of creating new tasks for humans,” says Daron Acemoglu, an MIT economist who studies automation and jobs.

The U.S. government incentivizes companies to automate, he says, by giving tax breaks for buying machinery and software. A business that pays a worker $100 pays $30 in taxes, but a business that spends $100 on equipment pays about $3 in taxes, he notes. The 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act lowered taxes on purchases so much that “you can actually make money buying equipment,” Acemoglu says.

In addition, artificial intelligence is becoming more adept at jobs that once were the purview of humans, making it harder for humans to stay ahead of machines. JPMorgan says it now has AI reviewing commercial-loan agreements, completing in seconds what used to take 360,000 hours of lawyers’ time over the course of a year. In May, amid plunging advertising revenue, Microsoft laid off dozens of journalists at MSN and its Microsoft News service, replacing them with AI that can scan and process content. Radio group iHeartMedia has laid off dozens of DJs to take advantage of its investments in technology and AI. I got help transcribing interviews for this story using Otter.ai, an AI-based transcription service. A few years ago, I might have paid $1 a minute for humans to do the same thing.

These advances make AI an easy choice for companies scrambling to cope during the pandemic. Municipalities that had to close their recycling facilities, where humans worked in close quarters, are using AI-assisted robots to sort through tons of plastic, paper and glass. AMP Robotics, the company that makes these robots, says inquiries from potential customers increased at least fivefold from March to June. Last year, 35 recycling facilities used AMP Robotics, says AMP spokesman Chris Wirth; by the end of 2020, nearly 100 will.

RDS Virginia, a recycling company in Virginia, purchased four AMP robots in 2019 for its Roanoke facility, deploying them on assembly lines to ensure the paper and plastic streams were free of misplaced materials. The robots could work around the clock, didn’t take bathroom breaks and didn’t require safety training, says Joe Benedetto, the company’s president. When the coronavirus hit, robots took over quality control as humans were pulled off assembly lines and given tasks that kept them at a safe distance from one another. Benedetto breathes easier knowing he won’t have to raise the robots’ pay to meet the minimum wage. He’s already thinking about where else he can deploy them. “There are a few reasons I prefer machinery,” Benedetto says. “For one thing, as long as you maintain it, it’s there every day to work.”

Companies deploying automation and AI say the technology allows them to create new jobs. But the number of new jobs is often minuscule compared with the number of jobs lost. LivePerson, which designs conversational software, could enable a company to take a 1,000-person call center and run it with 100 people plus chatbots, says CEO Rob LoCascio. A bot can respond to 10,000 queries in an hour, LoCascio says; an efficient call-center rep can answer six.

LivePerson saw a fourfold increase in demand in March as companies closed call centers, LoCascio says. “What happened was the contact-center representatives went home, and a lot of them can’t work from home,” he says.

Some surprising businesses are embracing automation. David’s Bridal, which sells wedding gowns and other formal wear in about 300 stores across North America and the U.K., set up a chatbot called Zoey through LivePerson last year. When the pandemic forced David’s Bridal to close its stores, Zoey helped manage customer inquiries flooding the company’s call centers, says Holly Carroll, vice president of the customer-service and contact center. Without a bot, “we would have been dead in the water,” Carroll says.

David’s Bridal now spends 35% less on call centers and can handle three times more messages through its chatbot than it can through voice or email. (Zoey may be cheaper than a human, but it is not infallible. Via text, Zoey promised to connect me to a virtual stylist, but I never heard back from it or the company.)

Many organizations will likely look to technology as they face budget cuts and need to reduce staff. “I don’t see us going back to the staffing levels we were at prior to COVID,” says Brian Pokorny, the director of information technologies for Otsego County in New York State, who has cut 10% of his staff because of pandemic-related budget issues. “So we need to look at things like AI to streamline government services and make us more efficient.”

Pokorny used a free trial from IBM’s Watson Assistant early in the pandemic and set up an AI-powered web chat to answer questions from the public, like whether the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, the county seat, had reopened. (It had, as of June 26, with limited capacity.) Now, Watson can answer 75% of the questions people ask, and Otsego County has started paying for the service, which Pokorny says costs “pennies” per conversation. Though the county now uses AI just for online chats, it plans to deploy a Watson virtual assistant that can answer phone calls. Around 36 states have deployed chatbots to respond to questions about the pandemic and available government services, according to the National Association of State Chief Information Officers.

IBM and LivePerson say that by creating AI, they’re freeing up humans to do more sophisticated tasks. Companies that contract with LivePerson still need “bot builders” to help teach the AI how to answer questions, and call-center agents see their pay increase by about 15% when they become bot builders, LoCascio says. “We can look at it like there’s going to be this massive job loss, or we can look at it that people get moved into different places and positions in the world to better their lives,” LoCascio says.

But companies will need far fewer bot builders than call-center agents, and mobility is not always an option, especially for workers without college degrees or whose employers do not offer retraining. Non-union workers are especially vulnerable. Larry Collins and his colleagues, represented by SEIU Local 1000, were fortunate: they’re being paid their full salaries for the foreseeable future in exchange for taking 32 hours a week of online classes in computer skills, accounting, entrepreneurship and other fields. (Some might even get their jobs back, albeit temporarily, as the state upgrades its systems.) But just 11.6 % of American workers were represented by a union in 2019.

Yvonne R. Walker, the union president, says most non-union workers don’t get this kind of assistance. “Companies out there don’t provide employee training and upskilling–they don’t see it as a good investment,” Walker says. “Unless workers have a union thinking about these things, the workers get left behind.”

In Sweden, employers pay into private funds that help workers get retrained; Singapore’s SkillsFuture program reimburses citizens up to 500 Singapore dollars (about $362 in U.S. currency) for approved retraining courses. But in the U.S., the most robust retraining programs are for workers whose jobs are sent overseas or otherwise lost because of trade issues. A few states have started promising to pay community-college tuition for adult learners who seek retraining; the Tennessee Reconnect program pays for adults over 25 without college degrees to get certificates, associate’s degrees and technical diplomas. But a similar program in Michigan is in jeopardy as states struggle with budget issues, says Michelle Miller-Adams, a researcher at the W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research.

House and Senate Democrats introduced a $15 billion workforce-retraining bill in early May, but it hasn’t gained much traction with Republicans, who prefer to encourage retraining by giving tax credits. The federal funds that exist come with restrictions. Pell Grants, which help low-income students pay for education, can’t be used for nontraditional programs like boot camps or a 170-hour EMT certification. Local jobless centers, which receive federal funds, spend an average of $3,500 per person on retraining, but they usually run out of money early in a calendar year because of limited funding, says Ayobami Olugbemiga, press secretary at the National Skills Coalition.

Even if federal funding were widely available, the surge of people who need retraining would be more than universities can handle, says Gabe Dalporto, the CEO of Udacity, which offers online courses in programming, data science, AI and more. “A billion people will lose their jobs over the next 10 years due to AI, and if anything, COVID has accelerated that by about nine years,” says Dalporto. “If you tried to reskill a billion people in the university system, you would break the university system.”

Dalporto says the coronavirus should be a wake-up call for the federal government to rethink how it funds education. “We have this model where we want to dump huge amounts of capital into very slow, noncareer-specific education,” Dalporto says. “If you just repurposed 10% of that, you could retrain 3 million people in about six months.”

Online education providers say they can provide retraining and upskilling on workers’ own timelines, and for less money than traditional schools. Coursera offers six-month courses for $39 to $79 a month that provide students with certifications needed for a variety of jobs, says CEO Jeff Maggioncalda. Once they’ve landed a job, they can then pursue a college degree online, he says. “This idea that you get job skills first, get the job, then get your college degree online while you’re working, I think for a lot of people will be more economically effective,” he says. In April, Coursera launched a Workforce Recovery Initiative that allows the unemployed in some states and other countries, including Colombia and Singapore, to learn for free until the end of the year.

Online learning providers can offer relatively inexpensive upskilling options because they don’t have guidance counselors, classrooms and other features of brick-and-mortar schools. But there could be more of a role for employers to provide those support systems going forward. Dalporto, who calls the wave of automation during COVID-19 “our economic Pearl Harbor,” argues that the government should provide a tax credit of $2,500 per upskilled worker to companies that provide retraining. He also suggests that company severance packages include $1,500 in retraining credits.

Some employers are turning to Guild Education, which works with employers to subsidize upskilling. A program it launched in May lets companies pay a fee to have Guild assist laid-off workers in finding new jobs. Employers see this as a way to create loyalty among these former employees, says Rachel Carlson, the CEO of Guild. “The most thoughtful consumer companies say, Employee for now, customer for life,” she says.

With the economy 30 million jobs short of what it had before the pandemic, though, workers and employers may not see much use in training for jobs that may not be available for months or even years. And not every worker is interested in studying data science, cloud computing or artificial intelligence.

But those who have found a way to move from dying fields to in-demand jobs are likely to do better. A few years ago, Tristen Alexander was a call-center rep at a Georgia power company when he took a six-month online course to earn a Google IT Support Professional Certificate. A Google scholarship covered the cost for Alexander, who has no college degree and was supporting his wife and two kids on about $38,000 a year. Alexander credits his certificate with helping him win a promotion and says he now earns more than $70,000 annually. What’s more, the promotion has given him a sense of job security. “I just think there’s a great need for everyone to learn something technical,” he tells me.

Of course, Alexander knows that technology may significantly change his job in the next decade, so he’s already planning his next step. By 2021, he wants to master the skill of testing computer systems to spot vulnerabilities to hackers and gain a certificate in that practice, known as penetration testing. It will all but guarantee him a job, he says, working alongside the technology that’s changing the world.

–With reporting by Alejandro de la Garza and Julia Zorthian/New York

A Trump Organization helicopter featured in the opening credits of “The Apprentice” with now-President Donald Trump is for sale.

The 1989 Sikorsky S-76B, painted red, white and blue, registration N76DT, is listed for sale without a price on controller.com. Helivalue, a helicopter appraisal business, values similar models at $400,000 to $950,000.

Eric Trump, the President’s son who has run the family business while his father is in the White House, confirmed the listing.

“We currently have three helicopters and with my father in Washington (and not even allowed to use them), we simply don’t need them all,” Trump wrote in an email. The aircraft are stationed in New York, Florida and Europe, and they’ll probably keep two located in the U.S., he said.

The helicopter was used by Trump to travel to the 2016 Republican convention in Cleveland, where he was officially made the party’s nominee.

According to the listing, the six-seater aircraft features African mahogany paneling, ecru/almond leather seats, with fittings, including seat belts, finished in gold.

A broker responsible for the sale, Emmanuel Dupuy, said that he couldn’t comment on the listing because the information was private.

The Trump Organization’s business includes hotels, which have suffered in the coronavirus pandemic.

Trump’s government-mandated 2019 financial disclosure, an inexact look into his assets and income, was released Friday evening and showed little change across properties such as his Mar-a-Lago and Doral resorts in Florida and his Washington hotel. Trump filed the 78-page report after getting an extension on its due date.

The Wikipedia article on NOTECHS was added to the Aviation category.

The Wikipedia article on NOTECHS was added to the Aviation category.